How to Drill Carbon Steel with Indexable Tools

Carbon steel is the backbone of modern manufacturing. From 1018 low-carbon brackets to tough 4140 shafts, it’s likely the material you machine most often. Yet, many shops are still losing money on hole-making because they are stuck using outdated tooling strategies.

If you are still relying on high-speed steel (HSS) twist drills for holes larger than half an inch, you are leaving significant productivity on the table.

At Accurate Cut, we see this bottleneck frequently. A shop invests in high-performance CNC centers but slows them down with slow-feed tooling. The solution lies in mastering indexable insert drills. These tools—often called U-drills or short-hole drills—can slash cycle times by 60% or more compared to traditional methods. But they require a different approach. You can’t just load them up and run them like a twist drill.

This guide covers the specific parameters, insert grades, and rigidity requirements you need to drill carbon steel efficiently using indexable tools.

Why Choose Indexable Drills for Carbon Steel?

The primary argument for indexable drilling is speed. While a standard cobalt drill might run at 60–90 SFM (Surface Feet per Minute) in carbon steel, a modern indexable drill can comfortably run at 600–900 SFM. That is an order of magnitude difference.

But beyond raw speed, there is the issue of process reliability.

The Efficiency Gain

In production scenarios involving medium carbon steel (like 1045), switching to indexable drills typically yields:

- 3x to 4x Faster Penetration Rates due to higher RPM and feed capabilities.

- Zero Regrinding Time: When an edge wears out, you simply index the insert. No trips to the tool room.

- Better Chip Management: The geometry of indexable inserts is designed to break chips aggressively, preventing the “bird’s nests” common with twist drills.

There is also a versatility factor. Unlike a solid drill, an indexable drill on a lathe can often be used as a boring bar for light finishing passes or to chamfer the hole edge, reducing the need for tool changes.

Pre-Drilling Requirements: Rigidity and Coolant

Before you put tool to metal, you need to ensure your machine environment is capable. Indexable drills are essentially single-point boring bars that drill. Because the cutting forces are not as balanced as a two-flute twist drill, they demand high rigidity.

Machine Stability

If your spindle has play, or your gibs are loose, an indexable drill will chatter. In carbon steel, this chatter kills insert life instantly. The tool needs to be held short and tight.

The Coolant Criticality

Here is what most suppliers won’t emphasize enough: Coolant pressure is not optional; it is your conveyor belt for chips.

In deep holes (anything over 3x diameter), the heat generated in carbon steel is immense. But more importantly, the chips need to be flushed out immediately. If chips pack in the flutes, the drill body will weld to the workpiece, likely destroying both the tool and the part.

- Minimum Requirement: Target 150 PSI for shallow holes.

- Ideal Requirement: For effective chip evacuation in production, 300 PSI through-spindle coolant is the standard.

- Concentration: Maintain a rich mix (8-10%) to provide the lubricity needed to prevent built-up edge (BUE) on the inserts.

Selecting the Right Insert Grades for Carbon Steel (ISO P)

Not all inserts are created equal. Carbon steel falls under the ISO P classification (marked blue on most charts).

When selecting inserts for your drill, you must understand that the two inserts—the central (inner) and the peripheral (outer)—perform very different jobs.

The Inner Insert (Center)

The speed at the absolute center of the drill is virtually zero. This insert pushes metal more than it cuts it.

- Requirement: Toughness.

- Recommendation: Choose a tougher grade (often PVD coated) that can withstand the crushing forces and slower speeds without chipping.

The Outer Insert (Peripheral)

This insert is traveling at the full Surface Speed (SFM). It takes the brunt of the heat and abrasive wear.

- Requirement: Wear Resistance.

- Recommendation: Choose a harder grade (often CVD coated) designed for high heat and speed.

Most manufacturers offer specific “drill grades” for ISO P steels. Using a generic “general purpose” milling insert here often leads to premature failure. For a deeper understanding of how to match specific layers to your material, read our drill insert coatings guide.

Setup and Alignment

Alignment is the silent killer of indexable drills. The tolerance for error is much tighter than with HSS drills.

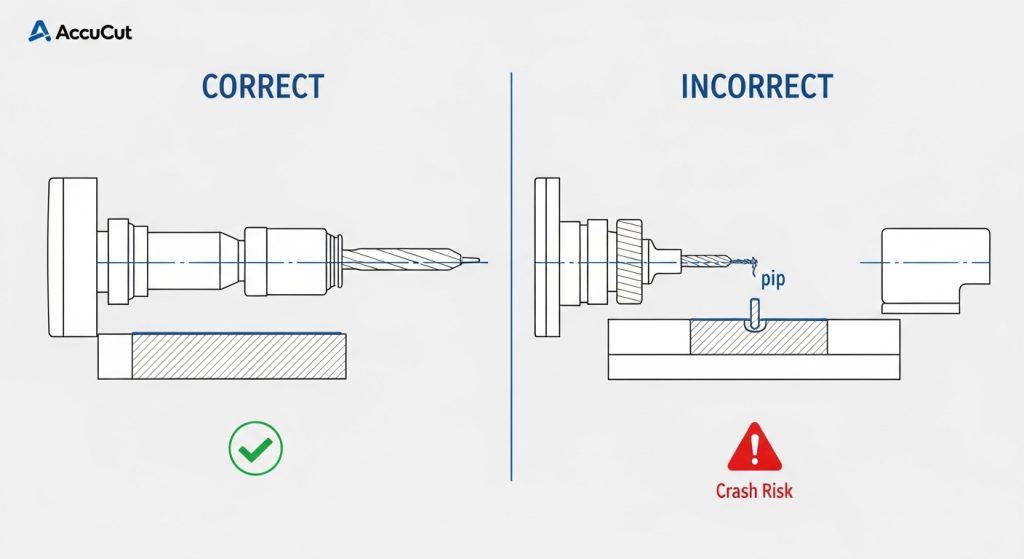

On the Lathe (Stationary Tool)

When the workpiece rotates and the tool is stationary, the drill tip must be exactly on the spindle centerline.

- The Tolerance: You need to be within 0.002″ (0.05mm) of center.

- The Risk: If the tool is below center, it will leave a “pip” or core in the middle of the hole. Eventually, this pip will grow large enough to hit the drill body, causing catastrophic failure. If it’s above center, the insert clearance angles are wrong, leading to rapid wear.

On the Mill (Rotating Tool)

Here, runout is the enemy. Use a high-quality hydraulic chuck or a side-lock end mill holder. Avoid ER collets for large diameter indexable drills if possible, as they may lack the rigidity required for the high feed rates.

Step-by-Step Guide: Drilling Parameters

Now, let’s look at the actual programming. Drilling carbon steel requires confidence—you have to commit to the cut.

1. Calculating Speed (SFM)

Start with the manufacturer’s recommendation for the specific grade, but a safe starting range for mild to medium carbon steel is 500–700 SFM.

Tip: If you run too slow, you may actually decrease tool life because the material tears rather than shears.

2. Calculating Feed (IPR)

Feed rate controls chip breaking. This is vital.

- Rule of Thumb: 0.002″ to 0.012″ per revolution (IPR), depending on diameter.

- For a 1-inch drill in 1045 steel, starting at 0.005–0.007 IPR is usually safe.

3. The “No Peck” Rule

This is the most common mistake operators make. Do not peck drill with indexable tools.

Pecking allows chips to fall back under the cutting edge. When the tool re-enters, it crunches those chips, fracturing the carbide inserts.

- Strategy: Drill in one continuous shot. If you have to clear chips, you need better coolant pressure or a different feed rate, not a peck cycle.

4. Entrance and Exit

- Entrance: If drilling into a flat surface, enter at 100% feed. If the surface is angled or uneven, reduce feed by 50% until the full diameter is engaged.

- Exit: When breaking through, the cutting forces drop rapidly, which can cause the “disc” of material to fly out or the drill to surge. It is often best to reduce feed by 25% for the last 0.050″ of the cut.

Troubleshooting Common Issues in Carbon Steel

Even with good parameters, carbon steel can be tricky. The material varies from batch to batch. Here is how to read the signs.

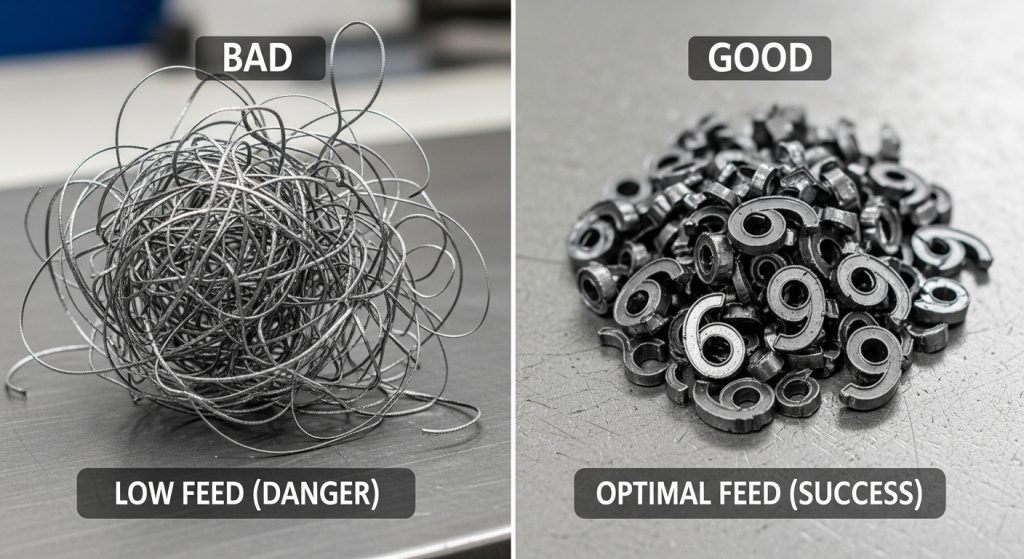

The Bottom Line on Chip Control

You want “6s and 9s”—chips that look like little commas.

- Long, Stringy Chips: The feed is too low. The chip is too thin to break under its own weight. Action: Increase feed rate.

- Tight, Broken Chips (Pepper): The feed might be too high, or the grade is too hard. While safe for evacuation, this can reduce insert life.

- Screaming/Chatter:

- Check center alignment.

- Check workholding rigidity.

- Try increasing the feed slightly to “load” the spindle and stabilize the cut.

- Reduce speed (RPM) to move out of the harmonic frequency.

Indexable vs. Solid Carbide: When to Use Which?

While we champion indexable tools, they aren’t the answer for every hole.

Use Indexable Drills When:

- Hole diameter is >0.500″ (12.7mm).

- Hole tolerance is loose (typically +/- 0.005″ to 0.010″).

- You need maximum material removal rates.

- You want to reduce tool inventory costs.

Stick to Solid Carbide When:

- Hole diameter is <0.375″.

- You need high precision (H7 tolerance).

- Surface finish requirements are critical (indexable drills can leave retraction marks).

- The setup lacks rigidity.

Conclusion

Drilling carbon steel efficiently is about balancing forces. With indexable tools, you trade the forgiveness of HSS for the raw performance of carbide. It requires a rigid setup and a commitment to proper feeds and speeds, but the payoff is undeniable.

By ensuring you have the correct ISO P inserts, high-pressure coolant, and a “no-peck” programming strategy, you can turn your drilling operations from a bottleneck into a competitive advantage.

At Accurate Cut, we specialize in optimizing these exact processes. If you are struggling with tool life or cycle times in your steel applications, it might be time to re-evaluate your tooling strategy.

Ready to optimize your drilling operations? Check our catalog for high-performance indexable drills or contact our technical team for a consultation.

FAQ

Can you peck drill with an indexable drill?

Generally, no. Pecking causes the brittle carbide inserts to impact previously cut chips upon re-entry, leading to chipping or fracture. Continuous feed is best. If chips aren’t breaking, adjust your feed rate or coolant pressure.

What is the best coolant pressure for drilling steel?

For indexable drilling in carbon steel, 150 PSI is the functional minimum. However, for holes deeper than 3x diameter, 300 PSI or higher is recommended to ensure chips are evacuated rapidly and heat is managed.

Why is my indexable drill making a screaming noise?

Screaming usually indicates chatter. This is often caused by the drill running too fast (RPM), the feed being too light (not stabilizing the cut), or the tool being off-center (especially on lathes).

Can indexable drills be used on a manual lathe?

It is possible but risky. Indexable drills require high RPM and constant, heavy feed rates that are difficult to maintain manually. They also lack the “self-centering” capability of twist drills, so the setup must be extremely rigid.

What is the difference between a U-drill and a Spade drill?

A U-drill (indexable insert drill) uses carbide inserts screwed into the periphery and center. A Spade drill uses a single replaceable blade that spans the full diameter. U-drills are generally faster for shallower holes, while spade drills are better for very large diameters or deep holes.