Solid vs. Indexable Drills: The Machinist’s Guide to Hole-Making ROI

Stop guessing which drill to buy. We break down the cost-per-hole, cycle time, and tolerance differences between Solid Carbide and Indexable drills so you can maximize ROI.

There is a specific sound every machinist knows—and dreads. It’s the “thump-crunch” of a drill body friction-welding itself inside a part because the coolant lines clogged or the feeds were pushed too hard.

I’ve walked past enough scrap bins in my 15 years on the floor to know that drilling usually accounts for a massive chunk of wasted production time. The debate between Solid Carbide and Indexable (Insert) Drills isn’t just about which tool looks cooler in the catalog. It’s about the physics of the cut, the logistics of your tool crib, and ultimately, your Cost Per Hole (CPH).

Many shops stick to what they know. If they grew up on HSS and Cobalt, they jump straight to Solid Carbide. If they run big production lots, they might overuse Indexable drills in places they don’t belong.

In this guide, we’re going to strip away the marketing fluff. We’ll look at the real-world ROI, the hidden costs of regrinding, and exactly when you should switch from one to the other.

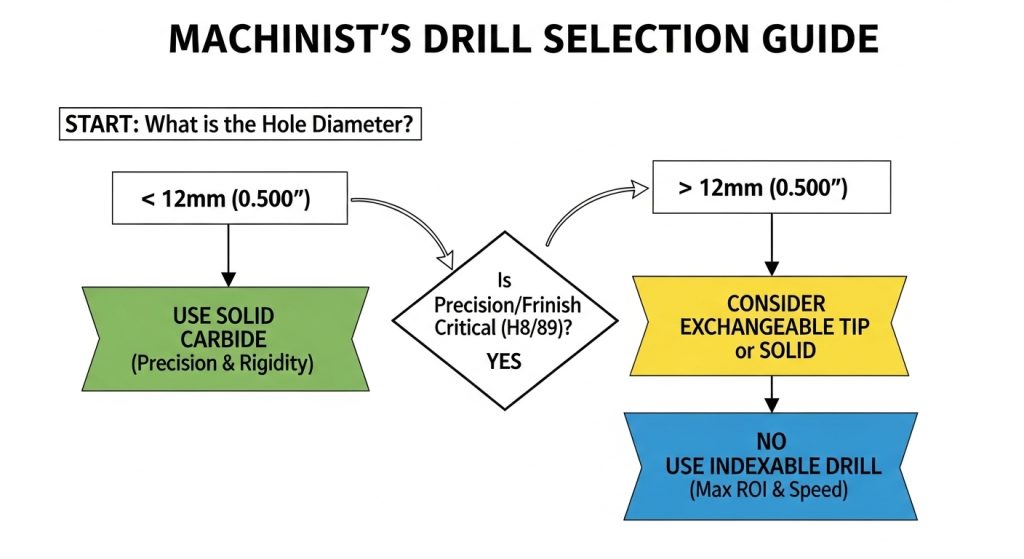

The “Diameter Rules”: Size Dictates Strategy

Before we talk about coatings or geometry, we have to talk about physics. The diameter of the hole you are making is usually the primary factor in choosing your tool type.

The Small Zone (<12mm / 0.500″)

If you are drilling under half an inch, Solid Carbide is almost always the undisputed king.

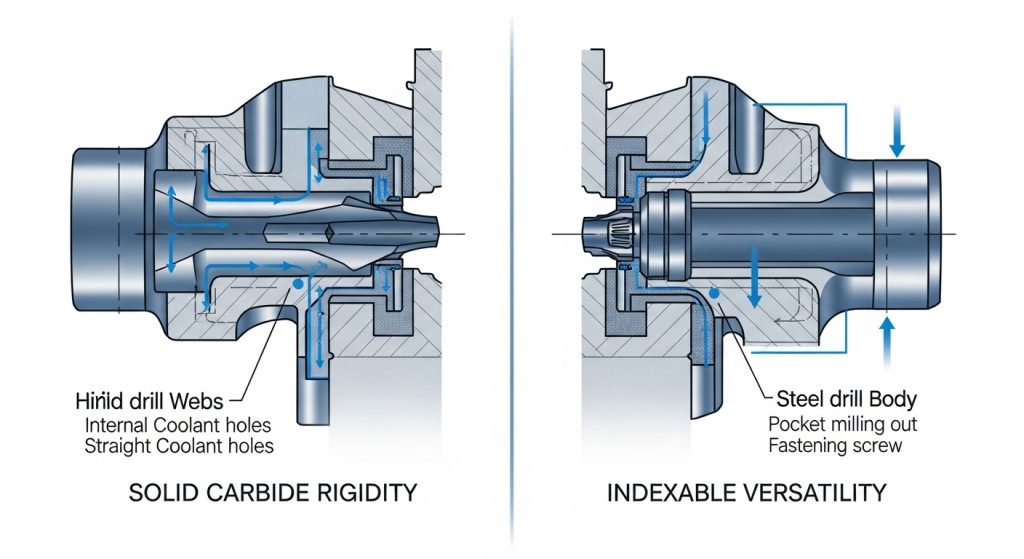

Why? It comes down to core strength. An indexable drill needs a steel body with pockets milled out to accept inserts. When you get below 12mm, there simply isn’t enough steel left in the drill body to hold an insert screw securely while maintaining rigidity. A solid carbide rod, however, is incredibly stiff. It resists deflection and delivers the coolant right to the tip without compromising structural integrity.

The Crossover Zone (12mm – 25mm / 0.500″ – 1.000″)

This is where the arguments happen in the engineering office. In this range, you have a choice. Solid carbide is still stronger and more accurate, but the price tag starts to climb exponentially.

- Solid Carbide: Expensive upfront, but precise.

- Indexable: Cheaper initial body, but less precise.

- The Hybrid Solution: This is the “Middle Child” that many suppliers ignore—Modular (Exchangeable Tip) Drills. These use a steel body but a solid carbide tip. They offer the precision of solid carbide with the cost benefits of a steel body. If you are in this zone, don’t overlook them.

The Large Zone (>25mm / 1.000″)

Once you pass the 1-inch mark, solid carbide becomes economically insane for general machining. A 40mm solid carbide drill would cost a fortune and weigh a ton. Here, Indexable Drills take over. The steel body is relatively cheap to manufacture, and you are only paying for the tiny carbide inserts that do the actual cutting.

Deep Dive: Solid Carbide Drills

When accuracy is non-negotiable, solid carbide is your best friend. These tools are ground from a single piece of micro-grain carbide.

The Pros: Precision and Finish

If your print calls for an ISO H8 or H9 tolerance, solid carbide is likely your only option without a secondary reaming operation. Because the flutes are ground continuously and the tool is perfectly balanced, it produces a superior surface finish (Ra).

Additionally, solid carbide is excellent for deep holes. I’ve run solid carbide drills at $30\times D$ (30 times diameter depth) successfully. You simply cannot do that with a standard indexable drill without massive deflection.

The Cons: The “Catastrophic Failure”

Here is the risk: Carbide is hard, which means it’s brittle. If a solid carbide drill jams or breaks, it shatters. You don’t just lose the cutting edge; you lose the entire $300 tool.

Best Applications

- High Precision: Holes requiring tight tolerances without reaming.

- Deep Holes: Anything deeper than $5\times D$.

- Unstable Setups: Ironically, because the tool itself is so rigid, it can sometimes handle a slightly less rigid setup better than an indexable drill, which relies on machine stiffness to prevent chatter.

Deep Dive: Indexable (Insert) Drills

An indexable drill is essentially a boring bar that can drill. It typically uses two inserts: a central insert and a peripheral (outer) insert. For a deeper look at how these tools function, check out our indexable drilling guide.

The Pros: MRR and Economics

The Material Removal Rate (MRR) on modern indexable drills is staggering. You can push these tools hard. But the real magic is in the Cost Per Edge. If you blow an edge, you just rotate the insert. A new edge costs a few dollars, not the price of a whole new tool.

The Cons: It’s a “Roughing” Tool

I tell my guys to treat indexable drills as roughers. You are generally looking at an H12 or H13 tolerance. They tend to drill slightly oversize, and when you retract the tool, the peripheral insert often drags along the wall, leaving a “spiral” mark. If you need a mirror finish, this isn’t the tool.

The Physics of the Cut

This is where most people get confused. The two inserts on an indexable drill are doing very different jobs:

- Inner Insert: Cuts to the center. At the very center of the drill, the Surface Feet per Minute (SFM) is effectively zero. This insert needs a tough grade of carbide to handle the shearing forces without chipping.

- Outer Insert: Runs at maximum SFM. This insert needs a wear-resistant grade to handle the heat and speed.

Pro Tip: If you aren’t using high-pressure coolant (at least 300 PSI through the spindle), be very careful with indexable drills. Their flutes are smaller than solid drills (due to the insert pocket), and chips can pack up quickly, leading to the dreaded “bird’s nest.”

The Hidden Costs: Calculating ROI

When you ask “Which is cheaper?”, you can’t just look at the invoice price. You have to look at the Logistics Cost.

The Regrind Trap

Solid carbide enthusiasts always say, “But you can regrind them 5 times!” True. But have you calculated the cost of that process?

- Inventory Float: To use regrinds effectively, you need three tools for every one active job: one in the machine, one in the crib, and one at the sharpening vendor.

- Performance Loss: A reground tool is rarely 100% as good as a new one. The coating may not be as slick, and the diameter will be slightly smaller, affecting your gauge line.

The Indexable Advantage

With indexable drills, your body lasts for hundreds, sometimes thousands of holes.

- Changeover Time: If an insert wears out, the operator can swap it while the tool is still in the machine spindle. That takes 2 minutes.

- Solid Carbide Swap: You have to take the holder out, put in a new drill, put it in the presetter to measure the new length (Z-offset), and update the machine. That’s a 10-15 minute process.

Bottom Line: If you are running high production, the downtime saved by indexable drills often pays for the tool body in the first week.

Selection Framework: The Drill Decision Matrix

Still not sure? Here is the cheat sheet I use when planning a process.

- Scenario A: Prototype / Low Volume: HSS or Solid Carbide. Don’t buy a $400 indexable body for a job that runs 50 parts.

- Scenario B: High Volume / High Precision: Solid Carbide. Swallow the cost to avoid the secondary reaming operation.

- Scenario C: High Volume / Loose Tolerance: Indexable. This is the sweet spot. Drill it fast, index the inserts, keep the spindle turning.

- Scenario D: Deep Holes ($>5\times D$): Solid Carbide. Indexable drills lose stability fast as they get longer.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Even experienced machinists get tripped up by these specific issues when switching between tool types.

Ignoring Coolant Pressure

Indexable drills are thirsty. Because the chips are broken into small “6s” and “9s” by the inserts, they need high pressure to flush them out. If you run an indexable drill on an old machine with a weak flood coolant pump, you will weld the tool to the part.

Lathe Turret Misalignment

On a mill, the tool spins. On a lathe, the part spins. If your lathe turret is off-center by even 0.002″, an indexable drill will leave a nasty “nub” at the bottom of the hole. This nub can destroy the inner insert instantly. Solid carbide is slightly more forgiving of this runout.

The “Pilot” Error

Never run a long indexable drill ($4\times D$ or longer) without a pilot hole. Unlike a solid drill which has a chisel edge to self-center, an indexable drill will wobble on entry, leading to a bell-mouthed hole or a snapped body.

FAQ: Quick Answers for the Shop Floor

Can you use indexable drills on a manual lathe?

Quick Answer: Generally, no. Indexable drills require high RPM and high thrust (Z-axis pressure) to engage the inserts properly. A manual machinist usually can’t hand-crank the tailstock hard enough or spin the chuck fast enough to make the carbide work. You’ll just rub the inserts until they glaze over. Stick to HSS or Cobalt for manual work.

What is the best drill for aluminum?

Quick Answer: It depends on volume. For highest quality, a polished solid carbide drill (specifically designed for aluminum) prevents chip welding. For high-volume material removal, you can use an indexable drill, but you must use specific PCD (diamond) or polished carbide inserts. Standard coated inserts will stick to the aluminum (built-up edge) and ruin the finish.

How many times can you regrind solid carbide?

Quick Answer: Typically 3 to 5 times. However, this depends on how badly worn the drill was before you pulled it. If you ran it until it chipped, you might not get any regrinds out of it. Pull the tool before catastrophic failure to maximize regrind life.

Conclusion

The choice between solid and indexable isn’t a “better or worse” conversation—it’s a “right tool for the job” conversation.

Here is the takeaway:

- Use Solid Carbide when the hole is small (<12mm), the tolerance is tight, or the hole is deep.

- Use Indexable Drills when the hole is large, the tolerance is loose, and you want to maximize uptime and reduce inventory headaches.

Don’t look at the price of the tool; look at the price of the hole. If an indexable drill saves you a secondary boring operation or cuts your cycle time in half, that $300 body is the cheapest tool in your shop.

Next Step: Go audit your tool crib. Are you using expensive solid carbide drills for 1-inch clearance holes? If so, you are literally throwing money into the chip conveyor. Call your supplier and ask to test an indexable body for those larger diameters.