What Features Matter Most in Indexable Drills

If you’ve spent enough time on a shop floor, you know the specific, sinking feeling of hearing a drill scream halfway through a deep hole. It usually ends with a loud pop, a spindle load monitor spiking to 100%, and a scrap part.

When we look at tooling catalogs, it’s easy to get fixated on the inserts—the coatings, the chip breakers, the grades. And don’t get me wrong, those are critical. But in my experience, the success or failure of an indexable drilling operation often comes down to the unspoken hero: the drill body itself.

You can put the world’s most advanced carbide insert into a cheap, unstable drill body, and you’ll still get chatter, poor surface finish, and premature failure.

At Accurate Cut, we view the indexable drill as a system, not just a consumable. Whether you are punching holes in 316 stainless or hogging out 4140 pre-hard, knowing what features to look for in the tool body can save you thousands in scrapped parts and machine downtime.

Here is what actually matters when selecting an indexable drill.

Drill Body Material and Hardness

Most suppliers won’t put this on the front page of their brochure, but the steel grade of the drill body is your foundation.

When you are drilling, especially at high feed rates, the heat generation is immense. The heat transfers from the insert directly into the pocket of the drill body. If the body material is too soft, it undergoes thermal expansion and contraction cycles that eventually deform the pocket. Once that pocket deforms—even by a few ten-thousandths of an inch—your insert loses rigidity.

What to look for:

- Hardened Tool Steel (H13 or similar): You want a body that is hardened to roughly 45–50 HRC. This hardness resists the abrasive wash of chips moving up the flute and prevents the insert pocket from “bell-mouthing” over time.

- Surface Treatment: Look for bodies with specialized surface treatments (like high-polish nickel plating or specific oxide coatings). This isn’t just for looks; it reduces friction to help chips slide up the flutes, preventing the dreaded “bird-nesting” that kills tool life.

Insert Pocket Precision and Stability

The number one killer of indexable drills isn’t speed—it’s vibration. And vibration starts in the pocket.

I’ve seen shops try to save $100 on a drill body only to burn through $500 worth of inserts a week because the pockets were loose. If the insert moves, even microscopically, it causes micro-chatter. This chips the cutting edge, leading to catastrophic failure.

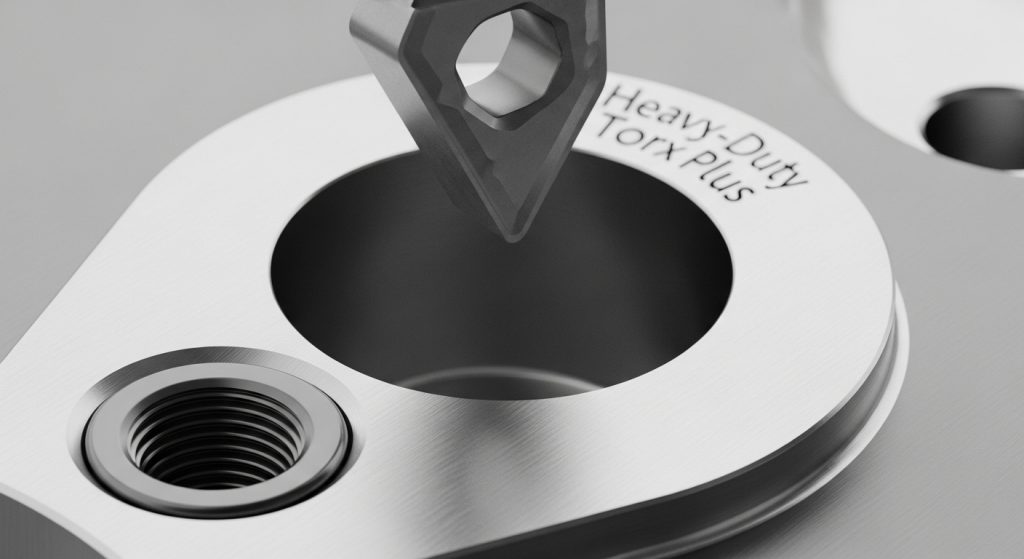

The Torx Plus Advantage

Ensure your drill uses Torx Plus screws rather than standard Torx. The geometry allows for higher torque without stripping the head, ensuring the insert is pulled firmly against the pocket walls.

The Dual-Insert Geometry (Inner vs. Outer)

If you look closely at a high-performance indexable drill, you’ll notice the inner and outer inserts often have different geometries or grades. This is intentional, and understanding it is key to optimization.

Here is the physics of it:

- The Central Insert: Cuts at virtually zero surface footage (SFM) near the center. It needs toughness to withstand the shearing forces and the “crushing” action at the center.

- The Peripheral (Outer) Insert: Cuts at maximum SFM. It generates the most heat and needs wear resistance.

Pro Tip: Don’t just default to using the same grade for both pockets. If you are drilling sticky materials like Stainless Steel (ISO M), consider a tougher grade on the inside to prevent chipping and a harder, coated grade on the outside to resist heat.

Coolant Delivery: The Lifeblood of the Tool

In solid carbide drilling, you can sometimes get away with flood coolant on shallow holes. With indexable drills, through-spindle coolant is virtually non-negotiable, especially once you go deeper than 2xD (2 times the diameter).

The coolant does two things here:

- It evacuates chips (volume is critical).

- It lubricates the wear pads on the drill body to maintain straightness.

The Pressure Rule

Check your machine’s coolant pressure. For indexable drills, you generally want at least 150 PSI for shallow holes, but if you are pushing 4xD or 5xD depths, you really need 300+ PSI. If the coolant can’t blast the chips out of the hole faster than you are making them, you will recut chips. Recutting chips breaks inserts instantly.

Shank Types: Weldon vs. Hydraulic

How you hold the drill is just as important as the drill itself.

- Weldon Flat (Side Lock): This is the industry standard for a reason. Indexable drills generate massive torque. A side-lock holder prevents the drill from rotating or pulling out of the holder.

- Hydraulic/Collet Chucks: These offer better run-out (concentricity), which can improve hole size accuracy. However, be very careful. Unless you are using a high-torque hydraulic chuck, the drilling forces can cause the tool to slip or pull out.

Safety Note: Never use a friction-only collet for large diameter indexable drilling. If the drill grabs, it can pull right out of the collet, crashing into your part and potentially damaging the machine spindle.

Cost-Per-Hole: The Real Math

It is tempting to buy a cheaper drill body. But let’s look at the ROI. A premium drill body might cost 30% more upfront but offer double the pocket life.

If a cheap body deforms after 500 holes, you have to replace it. If a quality body lasts 2,000 holes, your efficiency improves and your cost-per-hole drops significantly, even if the initial price tag was higher.

Conclusion: It’s a System

Selecting the right indexable drill comes down to rigidity, chip evacuation, and pocket life. By prioritizing a hardened steel body, precise pocket tolerances, and the right coolant delivery, you transform your drilling operations from a bottleneck into a reliable, high-speed process.

At Accurate Cut, we design our indexable solutions with these exact manufacturing realities in mind—tools built to handle the heat, the torque, and the volume of modern production.

Ready to optimize your hole-making process? Check out our range of high-performance indexable drills designed for longevity and precision.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the main advantage of an indexable drill over a spade drill?

Indexable drills generally run at much higher surface speeds (SFM) and feed rates than spade drills. While spade drills are excellent for very deep or large-diameter holes, indexable drills are faster and more efficient for high-volume production in the 2xD to 5xD range.

Why is my indexable drill making a high-pitched screaming noise?

This is usually “chatter.” It typically means one of three things: your surface speed is too high, your workholding is not rigid enough, or—most commonly—the drill is not perfectly on center. Check that your turret or spindle alignment is within 0.002″ of the centerline.

Can I use an indexable drill on a lathe and a mill?

Yes, but the setup differs. On a lathe (stationary drill, rotating part), alignment to the centerline is critical to prevent the “pip” at the bottom of the hole from breaking the inner insert. On a mill (rotating drill), you must ensure your workholding is rigid, as the drill enters the material with high impact.

Do I need to spot drill before using an indexable drill?

Generally, no. Indexable drills are designed to self-center. In fact, spotting can sometimes be detrimental if the spot drill angle doesn’t match the indexable drill angle perfectly, leading to corner chipping on entry. However, on very uneven surfaces (like castings), milling a small flat spot first is recommended.

What happens to the “disk” when the drill breaks through?

Unlike solid carbide drills that turn everything into chips, indexable drills often eject a small disk or “slug” when breaking through the material. Ensure your machine guarding is adequate, as this slug is ejected at high velocity and is very hot.